By Daniel McDermott, Dawn Konrad-Martin, Donald F. Austin, Susan Griest, Garnett P. McMillan and Stephen A. Fausti

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease that causes microvascular and neurologic complications and affects one in five veterans receiving care at the Veterans Administration (VA). Our research shows a link between diabetes and hearing loss and auditory brainstem function and suggests that patients with diabetes should be screened for hearing loss.

Understanding Diabetes

To understand why diabetes may affect hearing, it helps to understand how the body regulates blood sugar levels. Cells in the body require energy in the form of a simple sugar, glucose. The digestive tract breaks down the carbohydrates consumed into glucose, which is then absorbed into the bloodstream through the walls of the intestines. Once in the bloodstream, glucose is available as a cellular energy source. A flood of glucose is available after a meal, but this surge wanes in the hours between meals with no food intake. The body must manage these periods of feast and famine to maintain a stable level of glucose in the bloodstream.

When the body is functioning normally, the hormone insulin is released from the pancreas into the bloodstream at the start of the digestive process. Insulin helps move the glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where it is used as fuel in the near term. Insulin also helps move excess glucose into the liver, where it is stored for later use in the form of glycogen. As cells deplete their glucose supply, they restock by absorbing glucose from the bloodstream until that source runs low. Then a second hormone, glucagon, is released by the pancreas and stimulates the liver to release stored glucose (glycogen) into the bloodstream.

This system regulates blood sugar, keeping the blood sugar level in a healthy, narrow range. In patients with diabetes, however, the level of glucose in the bloodstream can fluctuate widely, with elevated levels immediately following large meals and dangerously low levels after periods without food.

This lack of control may be due to absence of insulin production by the pancreas (Type I diabetes) or inability to produce enough insulin (Type II diabetes). Type II is often accompanied by insulin resistance (i.e.,the body does not respond to its presence effectively), further exacerbating the problem. According to the American Diabetes Association, more than 90% of patients with diabetes have type II.

Low blood-sugar levels are an immediate threat to those with diabetes and can lead to confusion, loss of consciousness, and seizures. High blood-sugar levels are not an immediate danger, but if not controlled, can damage eyes, kidneys, and blood vessels and can impair the functioning of nerve pathways. Although less well-studied, damage from diabetes to blood vessels and nerves that could impact hearing has been suspected (Hirose, 2008).

Accumulating evidence points to a link between diabetes and hearing loss. In a recent study, Bainbridge et al. (2008) examined hearing data from 5,140 individuals who took part in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 1999 and 2004. Prevalence of hearing loss was 15% for participants without diabetes, but more than double for those with diabetes.

A recent study at the VA National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR) investigated a possible link between diabetes severity and hearing (Austin et al., 2009). A variety of severity measures were used, including whether or not insulin was needed. Bilateral pure-tone threshold results were obtained from the 302 participants (n = 604 ears).

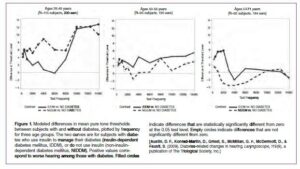

Figure 1 shows the estimated diabetes-related hearing impairment across a broad range of frequencies for three age groups. The heavy solid line in each panel represents the modeled difference of mean thresholds (in dB) between insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes and subjects without diabetes. The dashed line shows the threshold difference between noninsulin- dependent subjects with diabetes and subjects without diabetes. Positive values on each panel indicate that hearing is worse among subjects with diabetes compared with control subjects. Filled circles indicate that the difference is statistically significant after adjusting for correlations among ears and test frequencies. Open circles indicate that the difference is not statistically significant.

For insulin-dependent subjects, there was a significant effect of diabetes on hearing at some of the lower(speech) frequencies, even among older patients. However, the greatest effect of diabetes was for subjects under age 50 and at frequencies greater than 8 kHz, which are not routinely tested in the clinic. These younger subjects showed poorer thresholds, whether or not they used insulin. These results suggest that patients with diabetes—especially those who are younger—should be routinely screened for hearing loss. A protocol that includes extended high frequency testing may provide additional sensitivity to diabetes-related changes in hearing.

A number of recent studies have reported changes in central auditory processing associated with diabetes (Diaz de Leon-Morales et al., 2005). At NCRAR, auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) were examined in the same subjects that provided hearing results described above (Konrad-Martin et al., 2009). Group differences were found among subjects under age 50. For these younger subjects, ABRs adjusted for hearing at 3 kHz revealed abnormal central conduction times among subjects with insulindependent diabetes, but ABRs were normal in subjects with diabetes who did not require insulin. Thus, diabetes appears to affect hearing and brainstem function, and these effects appear somewhat independent.

Central auditory deficits can affect the ability to understand spoken language even when hearing is relatively normal. NCRAR is conducting further analyses to explore whether these same subjects with diabetes have difficulties understanding speech in noise or at a challenging rate. By specifically identifying the nature of the hearing problem, strategies for rehabilitation may be optimized.

Work supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration, and Office of Research and Development- Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) Service grants C3446R and C4447K.

References

National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (NDIC)

American Diabetes Association

Austin, D.F., Konrad-Martin, D., Griest, S., McMillan, G.P., McDermott, D., & Fausti, S. (2009). Diabetes-related changes in hearing. Laryngoscope, 119(9), 1788–1796.

Bainbridge, K.E., Hoffman, H.J., & Cowie, C.C. (2008). Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: Audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149, 1–10.

Diaz de Leon-Morales, L.V., Jauregui-Renaud, K., Garay-Sevilla, M.E., Hernande-Prado, J., Malacara-Hernandes, J.M. (2005). Auditory impairment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives medical Research, 36, 507–510.

Hirose, K. (2008). Hearing loss and diabetes: You might not know what you’re missing. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149, 54–55.

Konrad-Martin, D., Austin, D.F., Griest, S., McMillan, G.P., McDermott, D., & Fausti, S. (2009). Diabetes-related changes in auditory brainstem response. Laryngoscope, In Press.

The Link Between Diabetes and Hearing Loss

About the Authors

Daniel McDermott, MS, CCC-A, is a research audiologist at the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development’s National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR) at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon. Contact him at daniel.mcdermott@va.gov.

Dawn Konrad-Martin, PhD, CCC-A, is an investigator at the NCRAR and assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. Contact her at dawn.martin@va.gov.

Donald F. Austin, MD, MPH, is a research investigator at NCRAR and professor emeritus at the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. Contact him at donald.austin2@va.gov.

Susan Griest, MPH, is a biostatistician at the NCRAR and in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. Contact her at griests@ohsu.edu.

Garnett P. McMillan, PhD, is a biostatistician at NCRAR. Contact him at garnett.mcmillan@va.gov.

Stephen A. Fausti, PhD, CCC-A, is director of the NCRAR at the Portland VA Medical Center and professor in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. Contact him at stephen.fausti@va.gov.

Reprinted with permission from McDermott, D. , Konrad-Martin, D. , Austin, D. . , Griest, S. , McMillan, G. P. & Fausti, S. A. (2009, October 13). The Link Between Diabetes and Hearing Loss. The ASHA Leader.